What is a futures contract?

A futures is a contract and an obligation to deliver or to take delivery of an asset at a specified price on a specified future date. Buyers have the obligation to take delivery of the asset and to make payment for that asset by the pre-determined future date. Sellers have the obligation to deliver the asset and they have the right to collect payment from the buyers on a pre- determined date. Note that upon entering a futures contract trade, both buyers and sellers have obligations.

The underlying asset in a futures contract varies depending on the interest of the two parties involved in a trade. There are futures on financial indexes, corn, coffee, live hogs, pork bellies, gold, foreign exchange, and even on stocks. As it stands, you can trade a futures contract on just about anything.

Another attractive trait of futures contracts is the leverage. While stock bought on margin allows you to control the stock for 50% of its value, you can control a futures contract for as little as 5% of the asset’s value. This gives the futures trader tremendous purchasing power. Of course, leverage is a double-edged sword and traders have lived and died by this sword for centuries. In fact, a trader who makes a mere $5,000 investment in a futures contract could theoretically be exposed to $100,000 worth of downside risk. For this reason, brokerages that specialize in futures trading also require margin deposits. These are separated into two types: initial margins and maintenance margins.

The initial margin is the initial amount of money required to place a futures trade. It must be in the account before a trade is actually placed. This amount is determined by the exchange, but different brokers may have higher margin requirements.

Once a futures trade has been placed, you may at some point have to worry about maintenance margin. If your trade either does nothing, or better yet, goes in your favor, you do not have to worry about maintenance margin. However, if the trade goes against you, you may be asked to put up additional funds in order to fulfill your maintenance margin requirement. Maintenance margin requirements are what equities traders have come to know as “margin calls”. If you cannot come up with sufficient funds to support your position, your broker will most likely liquidate your trade at the market.

Given the massive exposure involved in futures trades, many traders intelligently look to hedge themselves with options. Hedging with options not only reduces the downside risk of a futures position, but it also may reduce the initial and maintenance requirements in your position. While hedging is the smart thing to do, you have to know the product you are trading. This is where many people get confused, so we’ll take some time to help you figure out the concepts.

What is so unique about options on futures?

Futures do not exist in every expiration month. They are traded in four (4) expiration months: March, June, September, and December. Each of these futures is denoted by one of four (4) letters: H (March), M (June), U (September), and Z (December). Therefore, the first thing you want to find out is which futures contract corresponds to the options you want to trade.

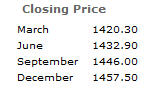

As an example, we will look at the S&P 500 futures traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (www.cme.com). They are denoted by the following symbols: SPH, SPM, SPU, and SPZ. The following are sample closing prices on the same day for each of the futures in 2007.

Note how the futures with the longer time frames trade for a higher value than those of shorter time frames. This is due to the fact that financial futures such as the S&P 500 futures have a cost of carry associated with them and this cost increases with more time to expiration (The fancy term for this is contango).

Now here’s the trick: Options on futures do exist in all 12 expiration months. Therefore, you must be aware of which futures contract your options are based off of. January, February, and March options pertain to the March future. April, May, and June options pertain to the June future. July, August, and September options pertain to the September future. October, November, and December options pertain to the December future.

Since all quarterly futures cycles behave the same way, we will focus on what happens during the first quarterly cycle. That is, we will explore the January, February, and March options and what happens as each approaches expiration.

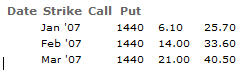

Take a look at the following option chain. It involves settlement prices for near-the-money options for the three months in question.

What we would like to do here is to use the options to gain an idea of where they imply that the future is trading. We gain the estimated futures level by the following formula:

Estimated Level = (Call Price – Put Price) + Strike

Plugging our numbers into the formula for each of the months, we get the following results:

Jan ’07: (6.10 – 25.70) + 1440 = 1420.40

Feb ’07: (14 – 33.6) + 1440 = 1420.40

Mar ’07: (21 – 40.50) + 1440 = 1420.50

This shows that all three option chains imply roughly the same future value. In fact, the March future settled at $1420.30 – give or take a dime, the options are all priced according to the level of the March future. This makes perfect sense since all three option months are priced directly off of the value of the March future.

So if the options all imply the same future level, why does it matter which one I choose to trade?

Here’s where it gets a bit tricky. If they are in the money at option expiration, the January and February options will settle to the March future as expected. However, depending on the March option you decide to trade, it will do one of two things: It will either settle to the March future OR it will cash settle. This all depends on whether you decided to trade theserial March option or the quarterly March option

How does this affect the collar trader?

Suppose you are long two S&P futures expiring in March 2007 (SPH07). For protection, you buy five January ’07 serial puts. Keep in mind that the multiplier of the S&P 500 future is 250. Hence, you would need to buy 5 puts in order to hedge all 500 units in your two futures contracts. You would then sell 5 January ’07 serial calls to help offset the cost of insurance assumed by the long puts. These January ’07 serial options will convert to March futures upon their expiration.

For example, suppose you bought the March futures for a price of $1421. Then suppose you bought the January ’07 1420 puts for protection and sold the January ’07 1430 calls to help offset the cost. At January expiration, if the futures close below $1420, your $1420 put will be in the money and will be converted to a short futures position at the strike (1420). This will offset the long contracts that you bought and you will be out of your trade.

On the other hand, if the future closes above $1430, your short calls will be in the money. It will then be converted to a short futures position at the strike (1430). This will also offset the long contracts that you bought and you will be out of your trade.

If the future closes between $1420 and $1430, both the short calls and the long puts will expire worthless and you will be left with a March future to hedge again, possibly with February ’07 options.

Note that when you use serial options to hedge a quarterly future, you run into possible pin risk situations. The scenario arises when the futures level at option expiration approaches the short call strike or the long put strike. It may be too close to call whether one of your options will expire in the money, thus helping you by automatically offsetting your position. Hence, after expiration, you may have a futures position to hedge or you may not. Given the tremendous leverage nvolved in being long a couple of futures contracts, you may want to take a more scientific approach to figuring out whether you would like to rehedge before entering the February option cycle.

We do this by utilizing the Expected Move formula. Using the implied volatility level of the short call or of the long put (it depends on which is more likely to become a factor at expiration), calculate a one day Expected Move per the formula. If the Expected Move will make the option in question go in the money, then there is a good chance that your position will be offset and you will not have to close the position out on your own. On the other hand, if the Expected Move will not be enough to make your option go in the money, your position will not be offset and you will likely want to think about protecting yourself going into the February options cycle.

Of course, there are no guarantees on what will actually happen, but short of always rehedging at a serial option expiration, this is a great educated guess at allowing you some peace of mind on options expiration.

Suppose instead that you buy 2 SPH07 contracts but this time you hedge with March quarterly options. At March expiration, both the options and the futures expire, so your March position will cash settle.

For example, let’s say you once again bought the March futures for a price of $1421. Now, however, you bought the March ’07 1420 puts for protection and sold the March ’07 1430 calls to help offset the cost. Let’s look at the following three scenarios:

Scenario 1: Futures close at $1433

At March expiration, the futures closed above the short strike (1430) by $3. Since you bought your futures for $1421, you would gain $6,000 ($12*500) on the futures portion of your trade. However, since your short 1430 calls would be in the money by $3, you would lose $1500 ($300*5) on the options portion of your trade. The 1420 puts would expire worthless.

Scenario 2: Futures close at $1415

At March expiration, the futures closed below the long strike (1420) by $5. Since you bought your futures for $1421, you would lose $3,000 ($6*500) on the futures portion of your trade. However, since your long 1420 puts would be in the money by $5, you would gain $2500 ($500*5) on the options portion of your trade. The 1430 call would expire worthless.

Scenario 3: Futures close at $1425

At March expiration, the futures closed in between your long put strike and your short call strike. Since you bought your futures for $1421, you would gain $2,000 ($4*500) on the futures portion of your trade. Your long 1420 put position and your short 1430 call position would expire worthless.

Thank you for investing the time in your future and success.