- Bid – Ask Basics

- Factors That Determine How Much You Can Shave

- How Much You Can Shave on an Individual Option

- How much can you save on a spread

- Criteria for a Spread

Our Books:

All Four Books

Liquid Book

Liquid Book One Strategy for All Markets

One Strategy for All Markets Option Greek for Profit

Option Greek for Profit Options Platinum

Options Platinum

Practicals

Practicals Stock Options and Collars

Stock Options and Collars Time Spreads

Time Spreads

Online Training:

Online Courses: 1-5 Remedial Videos

1-5 Remedial Videos BWB in 3 hours

BWB in 3 hours Collars Mini-Course

Collars Mini-Course Condor Copia Mini Course Recording

Condor Copia Mini Course Recording Online Platinum Class Recording

Online Platinum Class Recording Part-Time Trading Mini Course

Part-Time Trading Mini Course Scalping Class Recording

Scalping Class Recording

Videos & Books:

50/50 Video and Book

50/50 Video and Book Essentials Home Study Kit

Essentials Home Study Kit Practicals Home Study Kit

Practicals Home Study Kit

Live Events: Caribbean Cruise Seminar

Caribbean Cruise Seminar Italy Seminar

Italy Seminar

[/ezcol_1quarter]

Knowing the correct amount to shave can be tricky as there are no set rules. This section should help to put you in a position to save a good deal of money over the course of a trading year.

There are many people fighting hard to misinform you how much to shave. We do not believe this is out of maliciousness as much as out of ignorance or self-serving actions. Many people giving advice – the ignorant ones – have no clue what they are talking about, but this doesn’t stop them from dispensing their sophomoric thoughts. Brokers can also dispense misinformation out of laziness or impatience in getting their commissions. Furthermore, brokers sometimes find it easier to tell their client to pay “X” for a trade when the true rate is “X – $0.10.” Unfortunately, these brokers would rather hang up with the client instead of educating their client.

But brokers are in the ‘customer service’ business (an oxymoron in today’s business environment), and keeping their clients uneducated may be caused by a lack of knowledge or by complacency. We can’t judge, as we suspect it is more the former than the latter. We know that when Random Walk deals with clients we give 100%. We may still fail to please some people, but that doesn’t mean we don’t try.

This text will be broken down into various components. We will start with a short definition of the bid-ask spread designed for beginners. We will cover shaving for individual options, shaving the bid-ask spread for spreads, and the correct method of shaving the bid-ask spread for the One Strategy trade, which is the next strategy for you to learn after the basic course.

Bid

The “Bid” is the highest price the sum total of the marketplace is willing to pay for an instrument. If you wanted to buy a stock ABC for $20 when it was trading higher, you would have to wait for the stock to sell off since people are currently willing to pay more for it (otherwise it wouldn’t be trading higher than $20). Now suppose that the stock was trading at $21. If you were to put in a buy order for a price higher than where it is trading – $21.10 for example – you would set the bid price until someone sells you the stock.

Ask

The “Ask” price is the lowest price the sum total of the marketplace is willing to sell an instrument. You may have originally bought stock XYZ for $50, and now it is trading lower at $45. You may be thinking to yourself, “If the stock ever gets back to $50, I am selling this out and never trading the stock again.” Since the stock is lower than $50, no one would currently be willing to buy the stock for $50. Since someone else may be trying to sell the stock at $45, no one will consider buying your stock at $50. The ask price is $45 and will not be $50 until people buy all the stock available for sale all the way from $45 to $50.

Price Spread

The “Price Spread” is simply the difference between the bid price and ask price. A stock that is quoted $30.10 bid – $30.15 ask indicates that the stock’s highest price to buy right now is $30.10 and the stock’s lowest price to sell is $30.15. The price spread is $0.05 (30.15 ask – 30.10 bid = $0.05). Most brokers will quote the bid and ask prices so that the customer will know where he can fill immediately depending on whether he is buying or selling.

Shaving

Shaving the bid-ask spread means you are trying to cut back on giving up the entire bid-ask spread. If an option is priced $3.40 bid – $3.60 ask, you know that you can buy the option for $3.60 or sell the option at $3.40. In an attempt to buy the option for less, you place an order to buy the instrument for $3.50 (the middle of the bid-ask spread). This is what is referred to as “shaving;” you shaved the ask by $0.10.

A trader immediately wanting to buy this particular stock without the risk of missing the trade can likely do so for $30.15 (the ask price) which is the price the public is being quoted as wanting to sell. Someone immediately wanting to sell a stock can do so at $30.10 (the bid) because this is the highest price being quoted that people are willing to pay for the stock. The caveat is that nothing changes from the time you see the bid or ask price and the time you hit the send button to the broker.

Distance Between Bid-Ask in Percentages

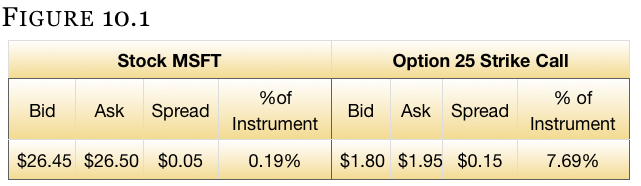

The price spread, or the bid and the ask prices, are both usually quoted with options just like they are with stock. However, the prices of the option’s bid-ask spread are usually measured as a percentage of investment – an even more important reason why you should attempt to shave the price of an option when possible. The box below illustrates the percentage lost on the bid-ask spread of an option compared to that of stock:

[ezcol_1half] [/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]Studying the Figure 10.1 shows the significant difference that the bid-ask spread plays on an option when compared to its underlying, the MSFT stock. When measured from the ask price, the bid-ask spread on the stock is only [/ezcol_1half_end]0.19% of the stock’s value whereas the bid-ask spread on the option makes up 7.69% of the value of your investment. This would be a concern for shaving but also more importantly because so much more can be made on a percentage basis on options rather than stock.

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]Studying the Figure 10.1 shows the significant difference that the bid-ask spread plays on an option when compared to its underlying, the MSFT stock. When measured from the ask price, the bid-ask spread on the stock is only [/ezcol_1half_end]0.19% of the stock’s value whereas the bid-ask spread on the option makes up 7.69% of the value of your investment. This would be a concern for shaving but also more importantly because so much more can be made on a percentage basis on options rather than stock.

How Much to Shave

The remaining portion of this text will deal with the correct amount to shave. By correct amount, we are speaking in general terms. Many things determine the amount you can cut into the market-maker’s perceived fee for entering into an option transaction. We say “perceived” fee since many people believe they have to give up the entire bid-ask spread according to their brokers. Brokers even have a name for this, The Natural. We are unsure how this name originated, but we know it is the price at which the broker will naturally receive his commission because you are almost certain of getting filled.

The remaining portion of this text will be divided into 4 primary sections:

- The factors that determine how much you can shave

- How much you can shave on an individual option

- How much you can shave on a spread

- The amount you can shave on a BWB trade as found in the One Strategy for all market ” book

Many factors are in play when determining the amount market-makers and the public are willing to give up with the bid-ask spread. In order of importance, they are supply and demand, liquidity, market trend, volatility of the underlying, the trend in volatility, etc. I will give an initial brief explanation of these factors here, and then I will pepper the text with examples for better understanding.

Supply and demand is the most significant and critical determining factor when considering the amount you can get away with shaving from the bid-ask spread. In a nutshell and in common terminology, the supply and demand is sum of all the other factors combined – the inventory, liquidity, psychology and trend – which afford the overall amount of what is going on with that instrument. If many people are long the option you are trying to purchase, it will obviously be much easier to find someone willing to sell the option rather than if most people were competing with you by being short the option and needing to buy it back.

Liquidity is the amount measured in volume that a particular option trades in a day. It is much easier to shave the bid-ask spread on an instrument that trades 20,000 contracts a day than it is for one that trades 20 contracts. The more consistently the option trades its volume throughout the day, the more liquid the option is as a rule. You would prefer to have an option that consistently trades 1, 2, 10 and 50 contracts throughout the day, rather than an option that trades the same volume in 1 big chunk throughout the day.

The more people trading that option the better it is for you. I have had people ask me, “If everyone knows your secrets, won’t it be more difficult to make money?” That will not happen for many reasons, especially laziness. 95% of the population will not better themselves if it requires the slightest amount of work. I could put the ideas of my text into the crib of every newborn in the world and 95% wouldn’t read it at any time during their life. Also, as more people are trading, liquidity is better which means you save getting in and out of trades.

Now if for some reason everyone on the planet read my materials and became better traders as a result, you still would not need to know more than 95% of the population. Instead, you would have to be more patient, intelligent, or disciplined than the other 95% of the population. No worries.

Another powerful force in determining how much you can shave is the overall trend of the market. People are sheep when acting in crowds. Natural market contrarians find difficulty bucking an over extended trend. If a trader were trying to purchase a call in a market where the stock is in a strong bull market, it would be more difficult for that trader to shave much, if any, of the bid-ask spread than it would be for a trader who is trying to sell the same option.

Think about this in terms of something more familiar. If you are trying to sell your used car because you really need the money and only one person shows up to look at it over the course of a week, you may be tempted to take any offer. If you have thirty people in your driveway looking under the hood and kicking the tires, the first thing you are going to think to yourself is, “I must have put the ad in the paper for too cheap of a listing price.” The same is true for options.

If you are competing to buy something, you will usually have to pay more than if everyone is competing to buy from you. If you want to buy a call because the market is climbing fast, you are probably not the only one wanting that option. Those who already do own the option, the ones who will be selling to you, are in no hurry to sell to you since they believe that every hour they wait to sell is more profit in their pockets.

As a general rule, the more quickly the stock/underlying is bouncing around, the wider the bid-ask spread and the more you will have to pay to play. During extreme periods of volatility on the floors, a condition known as a “Fast Market” is sometimes instituted allowing brokers and traders to widen out the bid-ask spread of the instruments farther apart than the regulated maximum distance normally determined by exchange rules. When an underlying is in a fast market condition, many traders commonly walk out of the pit to avoid making a costly mistake. Their leave would further decrease the amount you can shave since fewer players mean less liquidity.

Remember, most floor traders do not take a lot of risk. They like to hedge their options with stock until they can lock in profits through conversions, reversals, boxes, and jelly rolls. If the stock they are using to hedge their options is whip-sawing so much that they can not get an accurate estimate of where they can actually buy or sell the stock, they don’t want to trade. Their only recourse is to get more perceived edge on the option’s bid-ask spread to compensate for a potential loss on the stock’s swing.

Volatility trend is an overall perspective about volatility as measured by vega. This is very similar to market trend, but instead of the direction of the market determining if an option can be shaved, the trend in volatility determines if the price can be shaved.

If you are buying an option when the market’s volatility is increasing dramatically, giving up bid-ask is difficult. The volatility of the options is increasing because there is a dramatically larger amount of option buyers than option sellers that day. If you’re trying to buy, and everyone else is trying to buy, who is left to sell? Market-makers are required to sell by exchange rules, but they only have to sell at the ask price.

Suppose that volatility is decreasing in magnitude as measured by the VIX or by the stock’s underlying volatility, and you are trying to buy an option. The cause of the volatility crunch is that there are more people selling as opposed to buying options, and you may be one of the few people actually buying an option at that moment. You have a huge benefit which allows you to dramatically cut down the amount of the bid-ask spread you have to give up to purchase the option. As a matter of fact, there are times when you can put in an order to buy an option at the bid price during these conditions and get filled (provided all other variables remain constant and you are patient).

The supply and demand is the most powerful force when determining how much bid-ask spread you can shave.

The supply and demand is the overall effect of the other factors described; therefore, shaving becomes both an art and science of trading.. Knowing how much to shave can save a trader a fortune over the course of a year, let alone over the course of a career. We would actually venture to guess that many of our former floor trader colleagues would have been out of business if they gave up the bid-ask spread to the same extent that the average public investor did.

The box (MSFT) we looked at earlier showed that the bid-ask spread on a single option trade constitutes over 7% of the cost of the trade getting in, and then another 7% getting out when one gives up the entire bid-ask spread. That is huge, significant, and very costly. Think about it this way: calculate the total dollar value of all the options you trade over a given month. Annualize that number. Take that number and realize that about 15% of the number could be cut in half with intelligent shaving practices.

IMPORTANT

Shaving is NOT legging – do not confuse the two. When shaving the bid-ask spread you are not taking a directional opinion. You are simply trying to give the market-makers as little edge for themselves as possible to get into the trade. Legging is taking a directional bet hoping that the stock moves in the correct direction so that you get filled. Legging is a form of gambling. You will have winners and you will have losers. Like most people playing at the tables in Vegas, most (but not all) investors will lose more than they make on their winners. Random Walk advocates making intelligent investment decisions – not gambling.

This explanation is obviously based on options that have an average or wide bid-ask spread. There are some options that are so liquid that the bid-ask spread may be $0.05 or less. For example, $1.00 bid – $1.05 ask makes shaving nearly impossible and usually a waste of time.

[ezcol_1half] [/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

Shaving the bid-ask on an individual option (a simple buy/sell of a call/put) requires less patience than on a spread (like vertical) but also surprisingly has much to do with legging. It is also less of a factor on a single option than on a spread with two or more pieces. In other words, the more pieces to a trade, the more room you may have to negotiate. The explanation for these statements can be found easily in a discussion about delta.

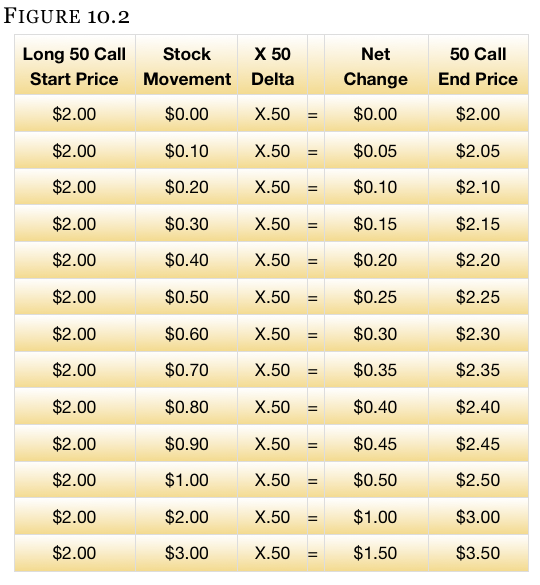

Recall from your texts the definition of delta. Delta is the amount an option moves when the stock/underlying moves $1. A single option will usually have a much higher delta than a spread would when using the same option as [/ezcol_1half_end]part of the spread. By definition, an ATM option has a delta of 0.50 meaning it will move $0.50 for every dollar the stock moves if all other variables remain constant. If the stock moves – even $0.30 on a 0.50 delta option – that is enough to change the price of an option by $0.15 (the entire width of the bid-ask spread in our MSFT example previously discussed). The stock’s $0.30 move multiplied by the option’s 0.50 delta is equivalent to a net $0.15 effect on the option ($0.30 x 0.50 = $0.15).

Figure 10.2 shows the effect that a stock’s movement has on a 50 delta option (Gamma is not considered in the table).

The answer goes back to the previous explanation of the factors affecting the bid-ask spread. As described in the caveat above (pertaining to options with a very tight bid-ask spread), you may just pay the whole bid-ask spread on such options. Again, you do not want to confuse gambling with shaving. Most options, however, have room to shave. When going into more volatile, illiquid or large indexes, you will have the opportunity to shave larger amounts.

1. Start with the mid-price between the bid-ask spread. An option that is trading $2.00 bid – $2.40 ask has a midpoint of $2.20. This is typical for some index options such as the OEX and SPX.

2. This midpoint is typically referred to as the fair value of the option. The fair value is what the typical worth of an option at that moment, and any buffer on either side of the midpoint is what the traders build in as an edge for themselves. Getting filled for buying or selling is difficult at this price unless a reciprocal order comes in at the same time or unless other factors (such as liquidity, market trend, etc.) are at work.

3. From this point, since you are giving edge to the market-makers, you will be adding money to the midpoint when buying or you will be lowering the price when selling unless the other variables discussed are working in your favor. An example would be when you are trying to buy a put. Suppose you are trying to buy this put (a bearish position) when the market is in a bullish trend and volatility is coming in, or getting lower. The fact that you are buying a bearish position in a bull market would allow you to get stingier about the amount of edge you give the market makers since people have a natural tendency to want to sell puts as the market is advancing. In addition, buying a put is buying volatility/vega. Volatility will decline because people are trying to aggressively sell options. When many people sell options, an option buyer has the advantage.

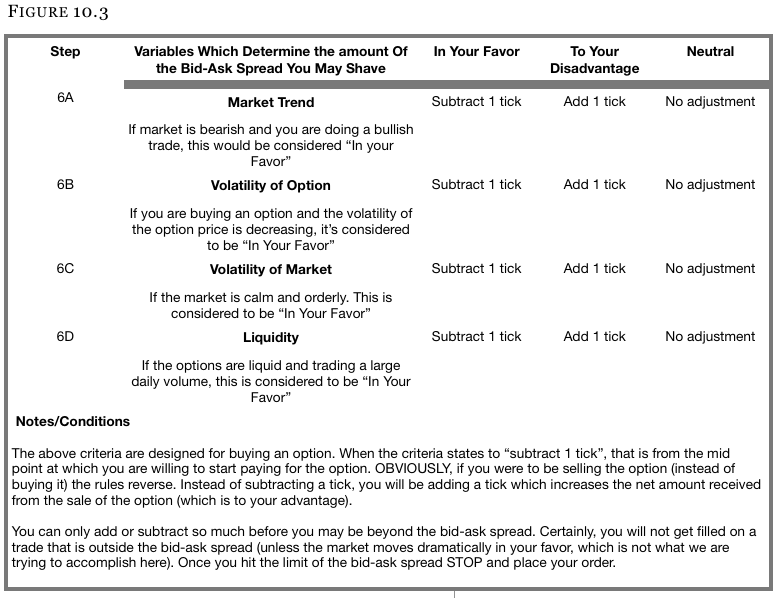

4. Once you understand steps 1-3, you will then want to adjust the midpoint of the option based on several factors. Keep in mind that if a condition, or variable, is working in your favor, you will be giving less edge, and if it is working against you, you may need to give more edge. Thus, if you are buying a call and the market is advancing, you are at a disadvantage for buying cheaply. However, if the market is declining, this is an advantage. Thus, the call will have to be priced higher to get filled in a bullish market than in a bearish market. We can’t stress enough that this is a typical example. Weird things happen all the time. You may be buying a call in a bullish market and some big trader decides to sell a huge portfolio of calls quickly by giving up the entire bid-ask spread. In that case, you would be filled on the bid if you had a standing order, but this is not typical.

5. Use the box below as a guideline for the thinking process behind determining how much you can shave. Also, don’t be surprised if you are talking directly to a broker and he criticizes your shaving. They only get paid when you get filled; it is in their best interest – and not your best interest – to pay the worst price or sell at the lowest price because it ensures a commission. Obviously, the bid-ask spread is not that wide. Even if the box below indicates you may want to pay more for something, the box is not suggesting you pay more than the ask price, or sell below the bid price.

6. You will begin by adding one tick if buying an option, or subtracting one tick if selling the option to the midpoint. If the midpoint is the fair value of the option, you have to give the trader some edge if you expect to get filled. “One tick” is the minimum increment an option can trade. Options under $3 have $0.05 increments. Options over $3 have $0.10 tick increments.

Example

We could take the criteria and plug in a hypothetical situation to illustrate how this works. Suppose that we want to purchase the OEX option discussed in Step #1 of the criteria. You will recall that the option was trading for $1.80 bid – $2.20 ask and has a midpoint of $2.00.

Assume that the option is a call that we are buying, volatility of the market is flat/normal, volatility of the options is increasing, the trend of the market is moving down, and liquidity is good. What do the criteria tell us to pay for this option?

To start, add one tick. Since we are buying the option and know the midpoint is $2.00, we will add a tick. Since the option is under $3, we will add $0.05 to the price we have to pay. Had we been selling the option we would have subtracted 1 tick.

This brings our entering bid price up to $2.05 from a midpoint of $2.00.

A. Market Trend – Since the trend is down and we are buying a bullish position (a long call or short put is bullish – a short call or long put is bearish), this is to our advantage. We will subtract one tick because this is to our advantage. If we were selling the option and the trend was to our advantage, we would add one tick to receive a higher sale price. This brings the bid price we will enter down to $2.00 (from $2.05 in the previous step).

B. Volatility of the Option – We are trying to buy an option in a market where the volatility is increasing which is most definitely to our disadvantage. As you will recall from the book Option Greeks For Profit, the vega of an option is the most powerful of all greeks. Because volatility is increasing we will have to add one tick. Selling an option with increasing volatility would have been to our advantage, regardless of whether we were selling a call or put.

This brings the bid price we will enter back up to $2.05 (from $2.00 in the previous step).

C. Volatility of the Market – Because the volatility of the market is normal we will not add or subtract in this step.

This leaves the bid price we will enter at $2.05 (from $2.05 in the previous step) – nothing changed.

D. Liquidity – The liquidity of the markets is good which is considered to be in your favor. This is a plus; as the more players in the market, the more likely someone will give up the bid-ask spread in your favor as well as in the other way. Because liquidity is in your favor, you may subtract one tick from the price you were willing to pay.

This brings the bid price we will enter down to $2.00 (from $2.05 in the previous step).

You now have the starting price from which you can enter the trade and have a better than 50/50 chance of getting filled if all other variables remain constant. We will begin by entering this trade to buy the call for $2.00. As luck would have it, this also happens to be the midpoint in this particular example.

A simple formula can be used as a starting point for very liquid stocks whose options are also very liquid (such as a popular index). Keep in mind that this is a guideline. Those who are not patient are free to expand the rules because they will find that waiting to get filled is often a boring and frustrating task. You also have to keep in mind how badly you might need to get filled. As your need to get filled increases, you may want to become more aggressive. We usually get very cheap when entering into a position, trying to keep the amount we are giving up in the bid-ask spread to an absolute minimum. Because we have no control over the market once we are in the trade, we may have to be very aggressive to get out at a loss or before we give back profit. Getting stingy on the way in often leaves more wiggle room on the way out. Real estate investors feel the same way as they often say, “The profit is made on the way into the deal.”

Also keep in mind that this is a guideline designed to work over long periods of time. On any given trade you may have been able to do better in hindsight, or you may miss the trade. It is our opinion that we would rather be bored than poor. We would rather wait to get filled, but still have more money in our pockets. You can always worsen the price later if you do not get filled in the amount of time you would like. In other words, if you don’t get filled, you can get more aggressive, but it is impossible to ask for a better price after you have already been filled. Then, you can only wish you originally placed the trade differently. Lastly, you should miss a trade rather than be in one that you don’t care for.

Shaving the market on a spread is exactly the same as a single option with a couple of exceptions and explanations.

First, spreads are generally less sensitive to price fluctuations in the stock/underlying than an individual option. Spreads also have more room to shave as there are at least two options in which shaving can be done. As such, shaving a spread is considered more of a necessity and less of a gamble as compared to an individual option.

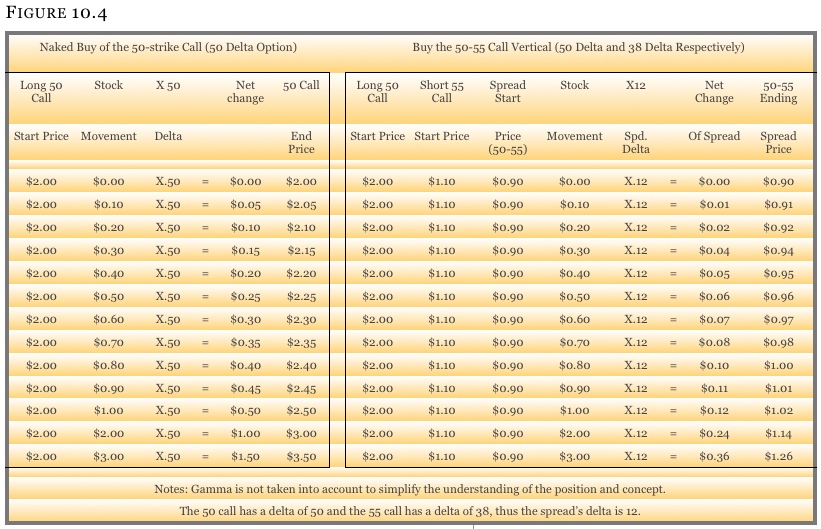

Figure10.4 illustrates a spread’s sensitivity to stock movement compared to that of the naked option described previously. You will see that for a given amount of movement in the stock, there is much less movement of the spread price than the naked option. For the “buy portion” of the long vertical spread, we will use the same 50 delta option purchased as a single option. We will then sell an option against it which has a delta of 38 to turn this into a vertical spread. The spread’s net delta will now be 12.

Figure10.4 shows a single option’s delta and how it could affect execution when shaving the bid-ask spread as compared to that of a spread which is almost inert. A $1 move in the price of the underlying will move the naked single option $0.50, an amount that will push the option outside the bid-ask spread area. The spread will move $0.12 for the same $1 move in the underlying. Even if the stock moves $1, you will not be hurt nearly as badly as if you missed the trade.

From here, shaving is done in a similar manner with the exception that the volatility swing of the options will not affect the spread price anywhere near as dramatically as a single option. When you buy or sell a spread, especially verticals (compared to time spreads), the volatility of the long and short options do a good job at virtually canceling each other out. In other words, you can skip step 6B when dealing with spreads.

Other than skipping step B, the process works exactly the same with a naked option but in slow motion by comparison.

Important

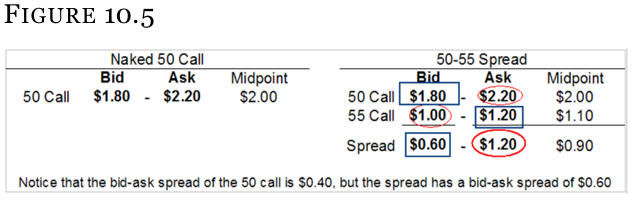

When looking at a spread to begin your shaving, you will look at the midpoint of the spread. This may be common sense, but forgetting to look at the midpoint is how mistakes are made or uncertainty originates. Both options, the buy and the sell, will have a midpoint. The difference in these midpoints is the spread’s midpoint.

This initially causes a little confusion. Since seeing is believing, we will borrow an idea from a floor trader friend and draw out the example.

If this confuses you, recall what is going on when you do a vertical spread. Slow yourself down and think it through. The worst price you could pay for a vertical (the ask of the spread circled) is buying the ask price of the 50 call and selling the bid price of the 55 call. In this example, it would cost you $1.20 to do this. The worst you could sell the spread (the bid price of the spread in rectangles) is accomplished by selling the 50 call on the bid and buying the 55 call on the ask, costing you $0.60.

Either way you slice it, the midpoint of the spread is $0.90. You can take the midpoint of the bid-ask spread or the difference in the midpoints of both options and come up with the same starting figure.

After you get the midpoint, the criteria for the spread is the same as the individual option with the exception that 6B won’t be needed. In other words, if you were buying the spread (as opposed to selling it), you would take the midpoint of $0.90 and add one tick ($0.05) to this price to get your starting point of $0.95. From here you will then add and subtract ticks based on steps 6A, 6C and 6D.

It is that simple. Once in the spread, you will perform the same process to exit the spread. The only difference, which was mentioned earlier, is that if you are losing money and have hit your exit point, then to curtail your losses, you likely will want to be more aggressive and less patient getting out.

How much you can shave on a “One Strategy” Spread

This will only make sense for those who own a copy of the One Strategy for All Markets book. You are obviously free to read it, but please do NOT feel like you understand the strategy simply because you looked at the example and think it makes sense.

This is a very powerful strategy that, if done correctly, can prevent a loss in almost any market condition. One of us had these positions going the wrong way during 9-11 when the markets closed 800 points lower in a single day, but she didn’t lose anything. The key is putting them on correctly and understanding why they work. If you don’t do this, you are almost assured of losing well over the cost of the book. We hate to see anyone lose money when it is preventable.

Very Important

The bid-ask spread criteria for the BWB works exactly the same as that of the regular spread. Our office staff occasionally gets emails from people stating that the strategy won’t work because you have to give up too much in bid-ask. NOPE! If you are shaving correctly you will NOT have problems getting into the trade. We often get into approximately 50% of the BWB trades we place without giving up any more than the original one tick from the mid price of all the pieces combined.

Elimination of Step A

Figure 10.6 is a 4 piece BWB trade (instead of a 3 piece) where we created a synthetic strike as described in the text. We purposely made this a little more difficult to facilitate your understanding, even though it may complicate things a tad more initially. You will see that the Bid-Ask works exactly the same way except that the delta of the spread is significantly lower than even that of a vertical spread; therefore, market direction isn’t a significant a factor. We will often put the same trade in for 5 days in a row in an index such as the Dow or OEX even though the market may be moving 100-200 Dow points a day. We will do so without having to adjust the price of the spread, thus step 6A as well as 6B can be eliminated with the BWB.

We can’t stress enough – if you are giving up too much bid-ask spread on this strategy, you are wasting money and you possibly won’t even be able to find a trade that meets the criteria since the entire spread’s bid-ask spread could be mind boggling. You are missing the point of the spread.An example is done with OEX option prices in Figure 10.6:

You will see that the net cost/credit of the spread is $0 using midpoints. Certainly, without argument, the cost could be astronomical if you bought it giving up the entire bid-ask spread on all the options. Even if you gave up 2/3 of the bid-ask spread, you still could not do this trade at the strikes mentioned. You would have to likely do the 580-570-535 for about even money as opposed to having the middle strike (the sale) synthetically being at $567.50. This $2.50 difference between what was actually done compared to what you would do if you gave away more bid-ask then necessary is a huge difference in potential profit and also in risk exposure. You would take a trade that potentially has 600 Dow points of protection to one that has only maybe 250-300 points.

We are being sincere when we say that we usually do not give up more than $0.10 – $0.20 of the total price (not the pieces) of the BWB trade to get filled perhaps 80% of the time. We literally get filled 50% of the time using the midpoint with no edge one way or the other. People who are saying that they cannot get filled because of the bid-ask spread have many excuses:

- Not patient enough.

- Not looking at the bid-ask spread correctly.

- Don’t understand the trade enough.

- You fill in the blank –